Retribution and Rhetoric in the NT Epistles – Brad Jersak with Peter Hordern

The following is a dialogue between Brad Jersak and Peter Hordern, about Pauls’ use of retribution language (in 2 Thessalonians 1), rhetorical criticism and the nonviolence of God.

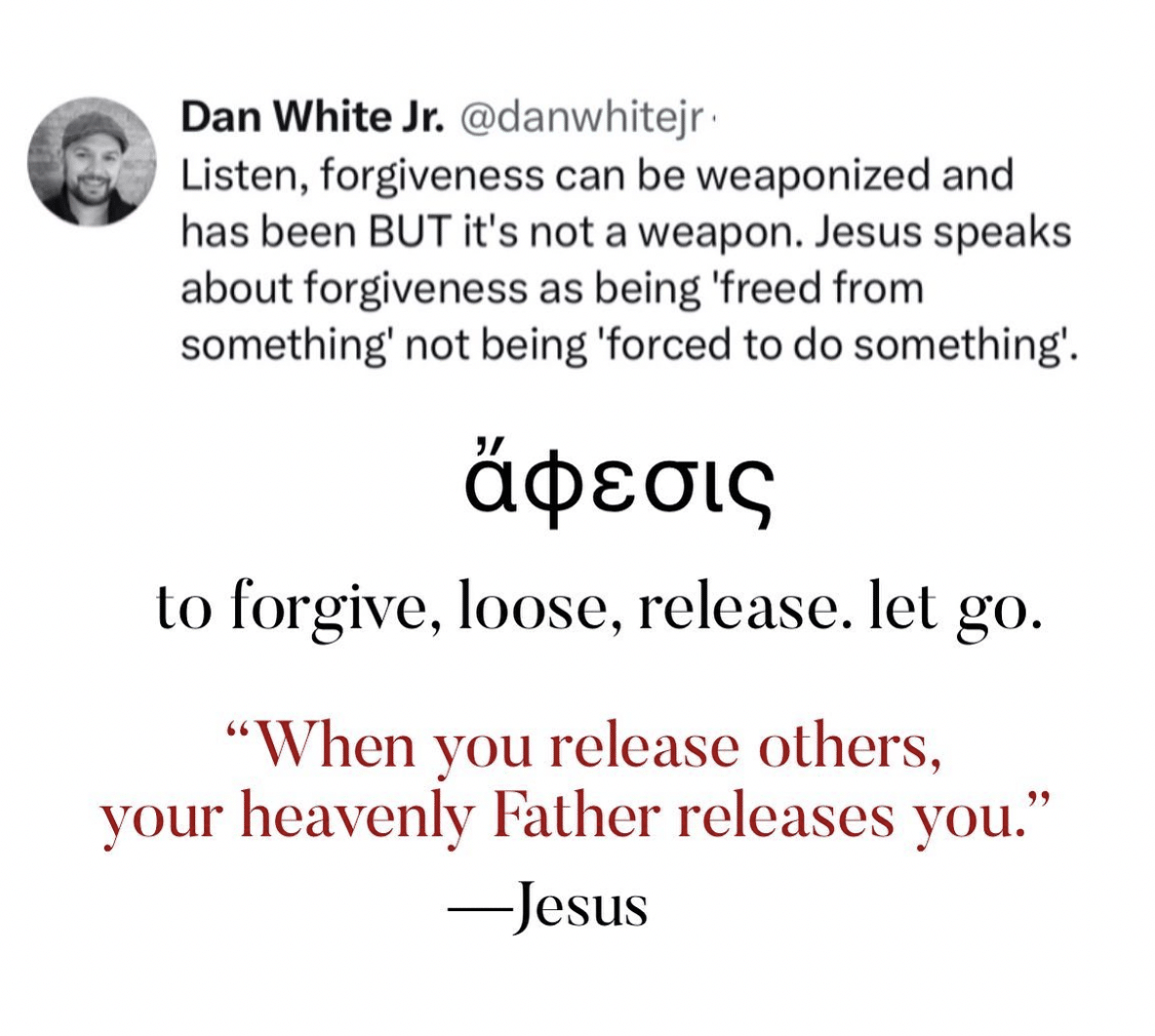

Peter: I’m continuing to wrestle with the idea of God as nonviolent. I feel like I see the truth of God’s nonviolence through Christ and his teachings, particularly on forgiveness. However, then I also read what Paul writes, especially in his epistles to the Thessalonians, which refer to end times and Gods punishment.

What do we do with that? Is it our wishful thinking that God really is as loving as we want Him to be? Or do we pass off Paul’s writings as a man trying to encourage a church in persecution with Gods justice, in order to give meaning to their suffering? Are there different translation possibilities? What do the words ‘punishment’ that Paul writes about really mean?

Brad: I do have some thoughts about this, as did certain church fathers like Clement of Alexandria (150-215 AD). First, he pointed out that Paul never uses the Greek words that we’d associate with retributive ‘punishment,’ but rather, always uses words best translated ‘correction.’ Let’s start with him. The following is an excerpt from my book, Her Gates Will Never Be Shut:

Clement’s importance, in my mind, is that he clarifies the New Testament language for “punishment.” (cf. esp. Paed. 1.5; 1.8 ANF 2). Clement insists that God’s “correction” (paideia—Heb 12:9) and “chastisement” (kolasis—Matt 25:46) is as a loving Father, only and always meant for the healing and salvation of the whole world. He denies that God ever inflicts “punishment” (timōria—Heb 10:29—vengeance) in the vengeful sense, a word Jesus never used. Watch how Clement ties judgment to correction with a view to redemption:

For all things are arranged with a view to the salvation of the universe by the Lord of the universe, both generally and particularly. . . But necessary corrections, through the goodness of the great overseeing Judge, both by the attendant angels, and by various acts of anticipative judgment, and by the perfect judgment, compel egregious sinners to repent. (Strom. 7.2 ANF 2).

… One can see how Clement read God’s corrective acts through the parental love emphasized in Heb 12:5–11, where we read that God disciplines those that he loves as dear children. For Clement, Providence uses corrections (padeiai) or chastisements (kolasis) when we fall away, but only for our good, only for our salvation. But God does not punish (timōria),which is retaliation for evil. (Strom. 7.16 ANF 2).

God deals with sin through correction, not punishment. That’s Clement, that’s Hebrews, that’s Hosea. The chastisements of God are disciplinary: not because divine justice demands satisfaction, payback, or wrath, but because a patient God is raising beloved children who tend to learn the hard way. The hardest lesson we learn is the lesson of the Cross: the jarring revelation that somehow each of us is complicit in the crucifixion of perfect Love (Zech 12:10), yet in love God forgave us (1 John 4:9–10). …

The Cross is a revelation of God’s love, our violence, and Jesus’ power to forgive and redeem—all at once. Don’t miss this point, because it marks a major fork in the theological trail. For centuries, I fear that we veered when Clement already had it right.

There are a also a few strange things at play in texts like 2 Thess. 1 and broader trends across the New Testament meta-narrative that require careful consideration. Here are a few starting points:

1. Across the Bible, including the NT and even within the language of Jesus, there are at times competing images and conflicting voices: Some of these voices (whether the voice of the accuser, the victim or the law) call for retribution and promising vengeance. But another voice — the voice of the Lamb (or sacrificial love) — clearly rejects retribution and renounces vengeance. Both sets are of voices are a sure fact of the text. I’ve written about this in detail elsewhere.

2. What becomes clear in the broad arc of biblical narrative is a trajectory where the language of vengeance and retribution is continually trumped by the Lamb’s voice forgiveness and restoration. This is the deeper, richer and more weighty voice within the prophets, Jesus and the apostolic writings.

For example, (a) “Vengeance is mine, I will repay” bows to “Father forgive them, bless them, don’t hold their sin to their account.” James’ epistle summarizes this principle as “Mercy triumphs over judgment” (James 2:13). In Paul, the ‘kindness of God’ trumps the ‘judgment of God’ (Romans 2:2-3). And in Christ, the perfection of the Father is seen in graciously granting sun and rain on the crops of the wicked and the righteous (Matt. 5:43-48) … clearly negating the covenant promises and threats of Deut. 28. Perhaps one could even say the vengeance language (what is due under the law) leads to the restoration language (what is promised under grace), a la Romans 6:23.

3. Still, how shall we read texts like 2 Thess. 1:3-10 (don’t skim this part … watch for the difficulties in italics):

3 We ought always to give thanks to God for you, brethren, as is only fitting, because your faith is greatly enlarged, and the love of each one of you toward one another grows ever greater; 4 therefore, we ourselves speak proudly of you among the churches of God for your perseverance and faith in the midst of all your persecutions and afflictions which you endure. 5 This is a plain indication of God’s righteous judgment so that you will be considered worthy of the kingdom of God, for which indeed you are suffering. 6 For after all it is only just for God to repay with affliction those who afflict you, 7 and to give relief to you who are afflicted and to us as well when the Lord Jesus will be revealed from heaven with His mighty angels in flaming fire, 8 dealing out retribution to those who do not know God and to those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. 9 These will pay the penalty of eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of His power, 10 when He comes to be glorified in His saints on that day, and to be marveled at among all who have believed—for our testimony to you was believed.

When I read this text, Clement’s categories of corrective judgment don’t seem so clear. What looks obvious to me here is that Paul is comforting a persecuted church by promising them payback, retribution, vengeance on those who’ve afflicted them. Now if Paul elsewhere overrides the language of retributive violence with Christ’s call to patiently endure and forgive persecutors (as he had been forgiven!), why appropriate this retribution rhetoric at all? Retribution ‘rhetoric’ — this is our first clue.

4. We are quite used to reading hyperbole as non-literal when it appears in Jesus parables, aphorisms or symbols of apocalypse. We know that hyperbole is a rhetorical device using exaggerated statements or claims to make a point and that they are not meant to be taken literally. For example, we know that Jesus never meant us to take him literally when he says we should cut off our hand and poke out our eye in order to be saved, We know that the judgement passages about sheep and goats are refering to nations, not domestic barn animals. And with any maturity in our interpretation, we won’t expect Jesus to streak across the sky on an actual flying horse with that a literal sword surging from his mouth. This is obvious in the New Testament genres of aphorisms, parables and apocalyptic language.

5. However … there is one common NT genre that is more difficult to spot and which we often fail to see. This is because it is embedded in among the didactic (teaching) material of the apostles letters (and an epistle is a genre in itself), This more eluse genre is the use of powerfully honed rhetoric. Whole schools of rhetoric existed in the cities and times where the epistles were written. Further, some of the NT authors were well-trained in rhetoric and use their rhetorical skills A LOT. So what is ‘rhetoric’?

‘Rhetoric’ is specifically a type of speech used in arguments to improve one’s persuasiveness. It appeals to a. the moral authority of one’s own character and argument, b. pathos or emotional appeal, and c. logos (or rational appear). Using these strategies is designed to create an emotional state in the listener/reader that will make them more suggestible to the arguments being given. In his Introduction to the New Testament, David DeSilva recalls Aristotle’s work, Rhetoric (1.2.3-4) and Quintilian (the master of rhetoric during Paul’s day). DeSilva describes the appeal to pathos this way:

A speaker could enhance the persuasive effects of an address by ‘putting the hearer into a certain frame of mind, that is, arousing emotions in the hearers that will move them in the direction the speaker wishes them to go. These are called appeals to pathos, or emotion. (DeSilva, 508) … Arousing emotions to move the hearers closer to taking the action or making the decision the speaker is promoting is always part of the strategy of persuasion. (DeSilva, 782).

To this day, the art of rhetoric is used everywhere from political speaches to courtroom closers to marketing campaigns to every revivalist’s pulpit-pounding. Knowing the types of ‘rhetoric’ the ancients were trained in enables us to see when the epistles are using rhetoric in their arguments.

‘Rhetoric’ of this kind includes quite an array. The following are examples of rhetorical tone that purposely appeal to the listeners’ emotions in order to sound more convincing:

- anger OR calm

- friendship OR enmity

- fear OR confidence

- shame OR favor

- pity

- indignation

- envy

- emulation

6. ‘Rhetorical criticism’ is an important element of NT interpretation which identifies rhetoric when it’s being used. The strange thing is that while ‘rhetoric’ can seem extremely manipulative, it is used all over the NT and some authors are absolute experts. We see a lot of rhetoric in books like Hebrews, 1 and 2 Thess, and 1 and 2 Peter. For example, one can see appeals to various forms of pathos throughout the book of Hebrews. DeSilva lays out these samples:

- Hebrews 4:14-16 – making them feel confident

- Hebrews 5:11-14 – making them feel shame

- Hebrews 10:26-31 – making them feel fear (and urgency)

- Hebrews 11:1-12:3 – making them feel praiseworthy

Sometimes these highly charged rhetorical devices are even used back to back, first flattering then threatening the reader, thus throwing the reader off balance, and again, putting them in an emotionally suggestible state. I find the apostles’ willingness to use rhetoric so brazenly a bit troubling, but there it is. The question is not whether or not they ‘go there’ — they obviously do — but how to read their use of rhetoric when interpreting a text.

Since they do, we are expected to recognize the rhetoric (just as we are meant to recognize poetry, parables or symbolic visions) and understand the flattery, threats or pathos at some level as non-literal, but without dismissing their important meaning. We need to read behind and beneath the rhetoric to identify the authors’ intent (and God’s message). Rather than interpreting their rhetoric woodenly (over-literally), we need to learn how to de-rhetoricize the text so as not to throw it in direct conflict with Christ and his apostles’ straightforward teachings on mercy, grace and forgiveness — and especially the way of the Cross, which God Incarnate not only taught but lived as the pre-eminent revelation of the non-violent God.

7. Finally, specifically on 2 Thess. 1, apart from the rhetorical elements (affirming them, then comforting them with vengence), Andrew Klager also pointed out some strange aspects of the text. He sees verse 5 as a real hinge in the chapter. When Paul says, “This is a plain indication of God’s righteous judgment,” isn’t it strange that he is actually referring even to the Thessalonians’ suffering under persecution as God’s judgment? And somehow this proves them worthy? VERY odd. And what might he mean by ‘judgment’? [kriseos, the same word used elsewhere for the wicked!]. Should we take this literally? And if not literally, then how shall we take it?

I have suggested elsewhere (here and here) that when Paul speaks of the judgments of God, his grid for this is usually ‘giving us over’ to sin’s consequences (3 times in Romans 1) … a kind of passive vengeance or wrath intrinsic to our self-destructive sin nature.

Klager offers a further insight on ‘the afflictions of God,’ If even the OT can reveal that God’s mercy endures forever, then Paul’s concept of judgment makes most sense when seen through the lens of Paul’s own conversion, namely ‘kicking against the goads,’ rather than an active retribution. Surely this is what the Thessalonian persecutors must face, just at Paul himself experienced.

8. But, we might ask, doesn’t Paul say that the Thessalonians persecution-judgment will come to an end at the Lord’s appearing? And on the other hand, doesn’t their persecutors’ judgment will be eternal? Again, citing my research from Her Gates (28-29):

The term “eternal punishment” goes back at least as far as Gregory and Augustine. Infernalists argue that “eternal” must mean everlasting in duration. Therefore, the punishment must be the forever and ever punitive torment of the wicked (as it is for the dragon and the beast in Rev 20). And the Universalists argue that “eternal” (aiōnios) can also literally mean an “age” (period of time) or an “unquantifiable duration of time.” If so, then one can make a case for a punishment of limited duration (as parts of 1 Enoch and the Talmud supposed). If the punishment is corrective and redemptive, aiōnion could mean that the chastisement continues for as long as is necessary to save the “goats.” The fact is: each side makes the case they prefer. Either is possible; neither is presumable. N.T. Wright offers a simple solution without tipping the scales:

“Aiōnian relates to the Greek aiōn, which often roughly translates the Hebrew olam. Some Jews thought of there being two “ages”— ha`olam ha-zeh, the present age, and ha`olam ha-ba, the age to come. Aiōnian punishment and the like would be punishment in the age to come.”

Thus, for Wright, aiōnion addresses the question of “when” rather than “how long.” Whatever the judgment or punishment is, it belongs to aiōnion, in the age to come. This resonates with me and does justice to the passage, reinforcing Jesus’ central point: how you live in this age impacts your life in the next age. In other words, Jesus will actually enforce the “golden rule.” This might sound a little like the Hindu concept of karma, but I prefer to think of it in terms of “sowing and reaping.”

Nik Ansell goes an important step further than Wright. For him, the judgment is not merely scheduled for the age to come; the birth pangs of judgment actually usher in the new age foretold by the prophets. God’s judgment is not meant to clear the wicked out of the path of the righteous, but to bring about the new era of hope for the salvation for all.

Peter: When I read your thoughts on Paul’s writings in 2 Thess. and the use of rhetoric in other books, it leaves me with this question: Is the only way to know it’s rhetoric by the language used (e.g. fear invoking…) or are there other indicators?

I’m imagining telling friends about this who would call themselves Reformed. I feel like they’d tell me that I’m twisting scripture to fit my view of a nonviolent God. Or is it possible to point to the text clearly that Paul and others are using it.

I think the fact that retribution-talk continues after Christ, and even among some of Jesus’ own disciples, makes the idea of a nonviolent God appear without full merit.

Obviously I’m basing this off the fact that most Christians (Evangelicals) read the threat of God’s vengeance at face value and completely literally. Even though there’s picking and choosing of what parts they read as literal and what parts are open to hyperbole and rhetoric.

Plain Truth Ministries | Box 300 | Pasadena, CA 91129-0300

Plain Truth Ministries | Box 300 | Pasadena, CA 91129-0300