Why Do Many Christians Make the Good News Sound So Weird? – Monte Wolverton

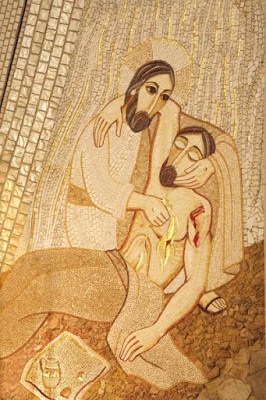

Among some folks, the ability to speak fluent “Christianese” is a sign of true Christianity. But do these special words and phrases help or hinder the message? Here’s some suggestions as to how we as Christ-followers might improve our communication skills.—Text and illustrations by Monte Wolverton

I just want to come up alongside you. I have a burden—because God has laid it on my heart to minister to you and disciple you. God spoke to me, and he wanted me to share my testimony with you and to witness to you. The message I’m called to give you will be a real blessing to you.

Chances are, you know some people who talk this way all the time. Maybe you are one. You might know others who don’t use this kind of language everywhere, but reserve it for use only when they are in the company of fellow Christians.

In certain groups, the ability to speak fluent Christian jargon seems to be the verification of true Christianity. Hundreds of thousands of well-meaning Christians talk this way because they believe it helps set them apart as God’s people. It’s their Christian jargon.

What Is Jargon?

Jargon (or in-speak) is a special set of words or phrases understood by a particular group.Jargon is useful. The world could not function without jargon. Just about every profession has a jargon. Musicians, publishers, computer software developers, lawyers and accountants use jargon. Psychology has a separate jargon for each of its several branches.

Jargon is really a kind of shorthand; one word can encompass a broad meaning. It might take paragraphs—or whole books—to explain the meaning of one word to the uninitiated.

Without jargon, communication on the job, or in a profession or in a field of knowledge would slow to a crawl.

But how many times have you been in a group of computer aficionados as they started throwing around terms like USB, I/O port, co-processor, jpeg and bandwidth?

Or perhaps you found yourself among a group of printers who started talking about bi-metal plates, blankets, slurring, density, web breaks and low folios.

If you’ve ever been in a situation like this, one of the following things might have happened:

• You pretend-ed to understand (and probably misunderstood) what everyone was talking about.

• You became bored and annoyed and wondered why the group was so socially inept and insensitive.

• You were intimidated and frustrated, so you left.

• You were impressed by the esoteric knowledge of the group, and you wanted to learn more about how to use these mysterious words.The last one probably didn’t happen.

The point is that if jargon is an aid to communication inside a particular group, it is a hindrance to communication outside the group.

Christian Jargon

Christian jargon (sometimes called “Christianese” falls into two categories.Theologyspeak. Christian clergy, theologians and theology students use some of these words—like sanctification and justification and predestination and the procession of the Holy Spirit.

Most of us don’t use these words in our everyday conversation—or at all, for that matter. It is simply not necessary for us to use them.

However, if you are a theologian, a member of the clergy or engaged in extensive study of Christian doctrine —you just can’t escape these words. For example, two theologians discussing supralapsarianism (a legitimate theological term whose meaning I cannot recall) would be at a distinct disadvantage if they could not use the word supralapsarianism.

They would either be compelled to explain the concept fully each time they mentioned it, or they would be forced to use vague replacement terms like whachamacallit.

Nevertheless, the quickest way for a pastor to cure a congregation’s insomnia is to announce: “Today I’m going to talk about double predestination.” It is a safe bet that if such theoogical jargon would put most Christians to sleep, any non-Christians would fall into a coma.

That’s one kind of Christian jargon. The other kind we’ll call: Evangelicalese. We’ll call the second kind of Christian jargon this because it seems to be lim-ited to the American evangelical community. Evangelicalese is largely absent from the mainstream Protestant denominations and the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches.

Since only a small minority of Christians really use Evangelicalese, calling it Christian jargon or Christianese would be a misnomer.

Evangelical Christians place great emphasis on evangelism, or sharing the good news about Jesus. Many evangelical Christians pride themselves in relating better to the average person on the street. Yet, ironically, many evangelicals insist on speaking a language that leaves the average person clueless.

Unfortunately, Evangelicalese is only the tip of the isolation iceberg for evangelical Christians. Because most evangelicals want a safe haven for themselves and their families, many have created their own culture—separate from the rest of the world.

But this is not what Jesus instructed. Before returning to heaven, he told his disciples, “Go into all the world and preach the good news to all creation” (Mark 16:15). While it is clear from other scriptures that Christians are to be separate from the evil in the world, we are to go into the world to share the good news. That implies that we should interact with people in our communities and that we should speak their language.

Some may claim that Evangelicalese is merely using biblical words, terms and phrases, with which there can certainly be nothing wrong, can there?

Yes and no.

Indeed, some terms and phrases used in Evangelicalese come right out of the Bible—and some don’t.

The ones that come out of the Bible usually come out of the 1611 King James Version (KJV)—and now, almost 500 years later, the meanings of most of those words have morphed into something quite different. And, of course, even if a word or phrase does come out of the KJV, most people don’t go around speaking 17th century English anymore.

In case you are not fluent in Evangelicalese, here’s a brief glossary of terms:

Disciple—”Hey, buddy! Have you been discipled yet? I’m going to disciple you!”

Our word disciple comes from a Latin word meaning “student.” But the Greek word translated “disciple” in the New Testament means more than “student.” It also means one who imitates his or her teacher.

But in Evangelicalese, disciple is often used as a verb. While it is nowhere translated as a verb in the KJV, a few scriptures use a Greek verb which means “to make a disciple” (Matthew 13:52; 27:57; 28:19; Acts 14:21).

It’s really a lot simpler to take a cue from some of the newer Bible translations. The New Century Version (NCV), for example, translates disciple as “follower.” In most cases, instead of using disciple as a verb, the Bible uses the words teach or instruct.

Instead of discipling people, we could simply instruct them or teach them. Isn’t that easy? Let’s try another.

Minister—”Do you mind if I just minister to you?”

In modern English the noun minister means pastor or clergy. A ministry is an institution involved in service. Evangelicalese takes it a step further and uses the word as a verb, so it sounds nice and biblical. But is there another term that might be more palatable to most people?In 2 Corinthians 3:6, we read, “Who also hath made us able ministers of the new testament…” (KJV). Contrast this with how it is translated in the NCV: “He made us able to be servants of a new agreement….” So what we really mean by ministry is just service. Why not say that?

Witness—”I was on my way to church Bingo, but I had to stop and witness to some sinners.”

This is a good Bible word—used hundreds of times in the KJV. It’s also used as part of our legal process. But is it the best word for Christians to use for sharing the story of Jesus with someone?

Acts 23:11 in the KJV reads: “Be of good cheer, Paul: for as thou hast testified of me in Jerusalem, so must thou bear witness also at Rome.”

The New International Version (NIV) reads: “Take courage! As you have testified about me in Jerusalem, so you must also testify in Rome.” The NCV reads: “Be brave. You have told people in Jerusalem about me. You must do the same in Rome.”

Telling people about Jesus. That sounds pretty natural. But no, evangelicals generally can’t just tell people—they have to “witness” to them.

Witnessing often implies that unless the “witnessee” accepts Jesus on the spot, your responsibility as a Christian is not over. The practice of witnessing can turn people into objects—tally marks on the cover of your Bible. But the Christian duty is to love all human beings, and the message of Christ is most effectively shared in the context of a sound friendship—not a random encounter.

Testimony—”I shared my testimony with the supermarket checker.”

This is sort of the same as witness. It’s a word out of the KJV that has been picked up and used by well-meaning Christians. In “real life,” testimony is something you give in court. People get uncomfortable when you tell them you’re going to share your testimony with them. Just tell them your story, and they’ll be happier.

Have a heart for—”She has a heart for ministry.”

While this is not a biblical phrase, it just sounds more spiritual than saying that someone has a preference or an aptitude—or—simply that someone loves to serve or is motivated to service.

Heart, however, is a biblical word, referring to the center of human mental and moral activity, both rational and emotional. In the ancient world, people did not realize that the brain was the center of mental activity. They believed that emotion and thought were housed in the heart or liver.

It is still popular to refer to the heart, metaphorically, as the center of emotion or motivation. But using the word heart in every other sentence can leave some people feeling as though they are swimming through a big vat of sentimental goo, a recreational activity which not everyone enjoys—least of all, men.

Anointed—”His preaching was anointed.”

In Evangelicalese—especially in charismatic circles, the word anointed or anointing is used excessively, almost as though it had magical properties. Biblically, anointing was a ritual dating from Old Testament times, involving the placing of olive oil on someone’s head to set them apart for the office of priest or king.

In New Testament times, the oil became symbolic of the Holy Spirit. The terms Messiah and Christ mean “the anointed one,” or one set apart by God for a specific duty or office—in this case Lord and Savior.

The ritual of anointing the sick is mentioned in James 5:14, however the NCV offers an alternative rendition of this scripture:

“Anyone who is sick should call the church’s elders. They should pray for and pour oil on the person in the name of the Lord.” Pour oil on doesn’t sound quite as spiritual as the term anointing—but it is.

The Bible also speaks of the anointing of the Holy Spirit that we as Christians receive through Jesus (1 John 2:27, NIV). But here the NCV replaces anointing with the simple word gift. When we say anointing, what we really mean is that a person has a special gift from God. Why not say that?

Come up alongside—”He came up alongside me in my hour of need.”

While this phrase is not found in the Bible, it is based on a Greek term which evokes a sort of nautical imagery of human companionship—of one vessel coming up alongside another. This can be pleasantly metaphorical the first time you hear it. Subsequent consistent, ad nauseum repetitions of this phrase become less pleasant.

Furthermore, many people may interpret your offer to “come up alongside” them as an invasion of their personal space. It’s much easier and safer to simply ask someone if they’d like to talk.

Perhaps you can think of several more Evangelicalese phrases and words.

Perhaps some terms and phrases are localized to your denomination or church. You can do what we’ve done in this article—look the phrase up in the Bible or dictionary, find out what it really means and find a more effective and less strange way to communicate your thoughts.

Plain Truth Ministries avoids Christian jargon. We make an effort to use “normal” English to make the good news about Jesus plain and clear. We believe that spiritual pride can be a product of Christian jargon. Christianese can often center on captives of religion, and who they think they are rather than who Jesus really is.

If you find yourself slipping into theological Christian jargon or popularized Evangelicalese, here are three things you can do.

1. Take note of the way people react to you as you talk with them. Do they look puzzled, confused, irritated—or perhaps even frightened? If they do, you probably need to take more care about the way you say what you say.

2. Find a good Bible translation or Bible paraphrase in contemporary English. Hundreds of translators, scholars and writers are working hard every day to bring God’s message to people in a way they can understand. There are many good products to choose from.

3. Talk about God in a normal, irreligious way. Others might actually understand you! Paul told us that he became all things to all men for the sake of the gospel (1 Corinthians 9:22-23). Many uses of Christian jargon seem to violate this principle.

There.

I’ve come up alongside you, witnessed, unloaded my burden and ministered to you.

Plain Truth Ministries | Box 300 | Pasadena, CA 91129-0300

Plain Truth Ministries | Box 300 | Pasadena, CA 91129-0300